VirTra Interview with Dr. Paul O’Connell

VirTra works with a variety of consultants and academics in police and use of force training. Dr. Paul O’Connell is one of those experts. VirTra recently spoke with him about the history of use of force training, his experience in a VirTra V-300 system and his own personal training experience as a sworn officer in the New York City Police Department. This is the second in a two-part blog series.

What was your training like as an officer in the NYPD?

I was hired as a NYPD officer immediately out of college in 1981. I was one of 1,200 recruits hired that class, and I’d never held a handgun. I went through five months of training on how to load, clean, and fire a gun. Back then the goal was to get an officer to learn to use his/her gun – there was not a proficiency continuum, but just ‘get the lessons and go’. There wasn’t a degree of competence required, and continuing training wasn’t part of the program. NYPD did have their own version of “Hogan’s Alley”, where they could practice car stops and limited situational plays that the instructors acted out. The idea was great, but the execution was pretty weak. Not every recruit was run through the situational training because of cost and time constraints. Veteran officers were exposed to this training too, but like the recruits, often only observed the performance of their fellow officers.

When the NYPD began instituting situational training for seasoned officers, they encountered another issue entirely: it was like a play where all the officers knew the ending. The training was highly scripted, and once the first officers went through the training, they shared their experiences with their fellow officers, and word spread on “what to expect.” Officers could prepare themselves in advance before they went through it. So at the end of the day it wasn’t all that effective.

The only other training I had during my time in the force was twice-annual shoots, indoor and outdoor range training for proficiency, and some training with moving targets. Like all other agencies at that time, there was little to no interactive training offered.

What did you think of the VirTra V-300 when you first experienced one of the scenarios?

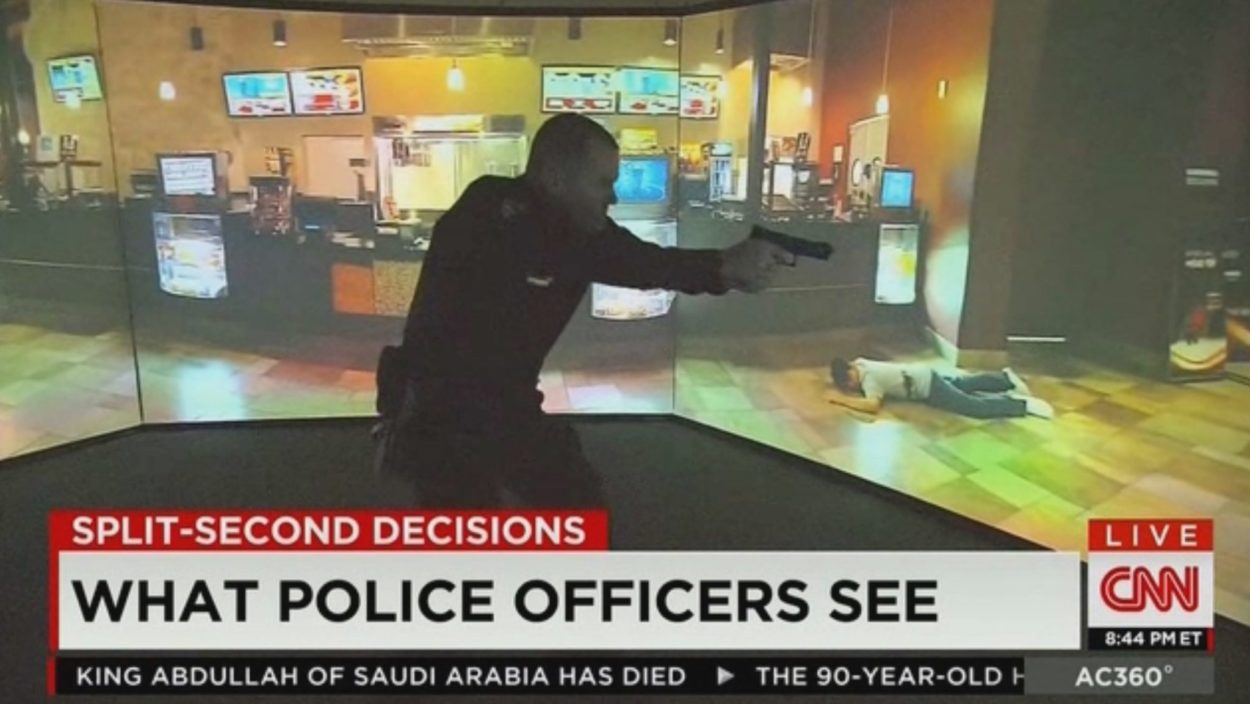

I first saw a V-300 at the Henderson, NV Police Department, and I was absolutely astounded at how realistic it is – things changing instantaneously as the situation unfolded – it was easy to lose yourself in the training. It was totally immersive. When it was over and the lights went on, my palms were sweaty, my hearing was elevated, and I had no idea how many shots I fired. It’s pretty amazing – VirTra now allows law enforcement to accomplish what they’ve been trying to do for the last 30-40 years – immerse the student in a situation that makes them think they are no longer going through an exercise. It’s the real thing, and the decision tree can literally branch off into a hundred different directions based on the areas the trainer feels that the officer needs to focus on. The prior machine didn’t have these options. It’s the art of illusion!

It’s an adrenaline dump, adrenaline rush. It makes you cold, makes you clammy and makes your mouth dry. This is where I want to learn from my failures. Instead of being out on the streets and failing there, this gives me an edge to fail here to succeed on the streets. – Seth Coleman, 11yr veteran Henderson PD

What I’ve seen from the Henderson Police Department is remarkable as well – they have perfected the debrief. As someone goes through these scenarios they are not only building muscle memory, they are adding skills around critical thinking in how to react and respond mentally to these incredibly stressful, life-like situations. The training in Henderson is top-notch.

How do you see use of force training evolving today?

The word of the day is “de-escalation training.” Officers don’t need lectures – they need to get put into a VirTra machine and have the lights turned off to see how tactically sound their judgment is so that officers can better recognize and mentally process the opportunities for de-escalation. Just because an officer is authorized to shoot, it doesn’t mean they should – de-escalation is critical. VirTra technology provides this – an immersive experience that allows those undergoing the training to see, hear, and experience the sights, sounds and other external stimuli that they would in a real-world situation. The ability to debrief immediately afterwards is huge – “here’s what you did, and here is another possible response.” That’s why I think some of the more questionable shootings are occurring today – officers don’t have a training experience or proper preparation to fall back on.

An effective training scenario is one that involves putting an officer into a situation and having an ability to slow things down, ask questions and interact dynamically. Done over time, the scenarios will help trainees say to themselves “I’ve seen this before – here’s what I need to do,” so that these situations become second nature and automatic. De-escalation training is about slowing things down. This was not available in the 80s or 90s, and if officers are not going through this type of training today, they are putting themselves, their departments and the community at risk.

Training in the past has been minimal and we’ve not done enough – you can’t cross your fingers and hope your officers do the right thing. VirTra helps departments build and staff a force that has a skillset with better communication skills and sharpen de-escalation tactics that can potentially diffuse a situation before use of force happens. Every law enforcement agency needs to ask themselves one fundamental question: How good is the judgment of your officers, and how good are they at talking to people?

VirTra gives trainers an ability to “interject” in a trainee or recruit’s training in a myriad of ways to help their brain comprehend and digest situations as they are happening. No other use of force training technology can replicate this level of realism.

Training is not a luxury, training is an absolute necessity. Look at the number of multi-million dollar settlements that are putting a drain on already-strapped state and local governments. Tens of millions of dollars in liability for “bad shootings.” That is not sustainable. Remediation and debrief of a scenario needs a more prominent place in any type of interactive training. The majority of the learning that occurs is not during the scenario, but rather through its evaluation. Students must experience success if they are to integrate future successful behaviors.

What steps can law enforcement leaders take to improve their training?

Police departments want to get better, but we need government and administrative support and funding. It’s going to require an up-front investment on their part – one that will pay dividends on the back-end in the form of better-trained officers who can respond more effectively and minimize risk for their departments and respective state or local governments. You can never eliminate risk, but you can actively manage and reduce it.

About Paul O’Connell, Ph.D., J.D.:

Recently Published

Join Our Newsletter