Omaha police officers are using force less often against the people they encounter on the streets, a change Chief Todd Schmaderer credits to beefed-up efforts to train and supervise cops before such events occur.

Police are learning techniques to resolve conflicts without force, sharpening their decision-making skills and being counseled to address personal problems that could affect how they react to stress at work.

Omaha Police Officer Matt Austin tests his decision-making skills using the VirTra judgment simulator at the Omaha Public Safety Training Center. Officers have seconds to decide how to react to varying situations.

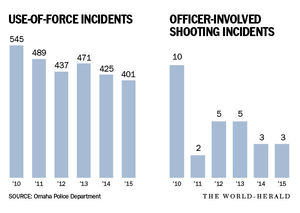

Use-of-force incidents dropped from 545 in 2010 to 401 by the end of December 2015, according to data provided by the Omaha Police Department. The numbers include any confirmed report of an officer using his or her fists, baton, pepper spray, Axon® TASER®, K-9 or gun while interacting with the public.

Public complaints of excessive force also went down, from 45 in 2010 to nine by the end of 2015.

Sgt. John Wells, head of the Omaha police union, said he appreciates the efforts to boost officer training, but he questioned what’s really behind the drop in use-of-force incidents. The reduction, he said, could be caused by the “Ferguson effect.”

In 2014, an officer fatally shot an unarmed black 18-year-old in Ferguson, Missouri, sparking protests and fueling discussions about policing across the country.

Since the Ferguson case, some argue, officers have become reluctant to initiate arrests for fear that civilians will record their actions and use the videos to challenge the police version of events.

“No cop wants to be a pariah,” Wells said. “It used to be, ‘Dear God, let me come home tonight.’ Now it’s, ‘Dear God, don’t let me wind up on YouTube.’ ”

Even though use-of-force numbers already were dropping in the city, Schmaderer said he decided that he needed to take an aggressive approach after a March 2013 incident in north Omaha. The incident outraged the black community and led to calls for independent oversight of police officers’ actions.

Officer Bradley Canterbury was seen on video throwing Octavious Johnson to the ground and hitting him repeatedly. Officers had arrived at Johnson’s house at 33rd and Seward Streets to tow his vehicle for unpaid parking tickets. The footage, shot on a neighbor’s cellphone, went viral.

Canterbury later said he used force because Johnson kept resisting commands.

Police also entered and searched the Johnson family’s home without a warrant, and Officer James Kinsella took a memory card out of a cellphone.

Schmaderer fired six officers, including Canterbury and Kinsella. Canterbury and another officer got their jobs back through arbitration.

After the incident, Schmaderer asked his staff to develop new training plans for new recruits and current officers, including supervisors. Part of that involved implementing a realistic training system called VirTra that police academy instructors began using to teach officers to think quickly and determine whether to use force — including whether to shoot.

Housed at the city’s police and fire training academy, VirTra, which was paid for by the Omaha Police Foundation, is located in a room with three floor-to-ceiling video screens that are set up in a half-circle. Each officer is given a Glock handgun converted to operate on compressed air. It matches the weight and feel of their service weapons.

The screens display a variety of potentially stressful situations that officers find themselves in daily, such as traffic stops. A trainer, using a computer program, selects the actors’ responses from among several options. The exercise tests officers’ decision-making skills because they have seconds to decide how to react.

If the officer fires his or her weapon, infrared screen sensors detect where a “bullet” hits. The officers also can use words, including commands, to try to defuse a situation before resorting to force.

Officials say events such as the Ferguson case, as well as incidents in Omaha, point to the need for the type of decision-making training that the department is providing. The most recent academy class, which graduated in December, was the first to go through the training. Other officers in the department have gone through it at least once.

As with other use-of-force incidents, the number of cases in which officers fired their guns has declined, going from 10 in 2010 to three last year. Of the 28 officer-involved shootings over that time period, 14 were fatal.

On Jan. 28 of this year, police say, an officer shot William A. Adams, 33, when Adams pulled a gun from his mouth and lowered it toward officers in the doorway of his apartment. Williams died the next day.

Knowing when to shoot or not is “a skill that if you don’t keep sharpened, you could become complacent,” said Capt. Michael McGee, who oversees academy training. “You’ve got milliseconds to make that decision.”

Schmaderer also sought out Weysan Dun, the former special agent in charge of the Omaha FBI office, to work with police supervisors on setting examples for their crews in such areas as ethics, public trust, accountability and public image.

Though Dun’s training didn’t specifically focus on use of force, the topics he covered all are part of the equation, Schmaderer said.

“Police officers are held to a very high standard because of the trust the public places on us,” Dun said. “The way any department operates is a reflection of its senior leadership, and, more importantly, how they handle themselves when dealing with the public and with each other.”

The Nebraska chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, which had voiced concerns over officer conduct after the 33rd and Seward incident, welcomed the focus on police resolving conflicts without force.

“We urge the department to continue steps toward increased accountability and independent oversight,” said Amy Miller, ACLU Nebraska’s legal director. “The drop in use-of-force incidents from the Omaha Police Department confirms how effective common-sense solutions can be.”

Officers do their jobs of protecting public safety best, she said, when they have ongoing training to address bias and de-escalation, “as well as clear policies related to use of force.”

Across the country, law enforcement agencies are making similar efforts. In Kansas City, for example, officers undergo “tactical disengagement” training in an effort to reduce use-of-force incidents. Instead of physical force, officers there try to use words to calm or “disengage” a suspect.

But not all are on board with the trend. In a February 2015 newsletter, the former president of the International Association of Police Chiefs expressed concerns that officers would hesitate when threatened and get themselves or others killed.

D’Shawn Cunningham, the founder of For the People, an Omaha group formed in 2013 that has been critical of police behavior, said he has met with Schmaderer to talk about excessive force and better police oversight. He said from what he’s hearing in north Omaha, relations with police have improved.

“Even informally, you don’t hear about officer assaults anymore,” Cunningham said. “What we used to hear a lot about was people getting pulled over and roughed up, or roughed up at a house party. We really don’t hear about it as much.”

The U.S. Department of Justice has said it applauds de-escalation training, saying it encourages officers to focus on respecting everyone they come across.

“The bottom line is we want to treat people the way we want to be treated,” Schmaderer said.

In Omaha, the Police Department’s Peer Support Program, which began in 2013, also has helped reduce use-of-force incidents, said McGee, the training captain. Officers who are having problems with work stress are encouraged to talk it through with one of their colleagues to better deal with any aggression that they might bring to their jobs.

McGee, who has been an officer for 30 years, said the way officers respond to offers of help is different from when he started. Back then, he said, police were reluctant to talk about job stress, fearing that they would be viewed as weak. “I can see the difference,” he said. “If I’m in a better mind set coming back to work, I’m less likely to overreact when encountering a stressful situation.”

Another part of Schmaderer’s efforts involves the department’s internal affairs unit, which investigates officer misconduct. The chief added a captain to the unit, Tom Shaffer, who, among his duties, oversees a conduct-tracking system. The system looks at internal reports filed by supervisors. It detects, among other things, when officers are involved in three or more use-of-force incidents in a three-month time frame.

The sergeant in charge of the officer is notified and will sit down with him or her to talk about the incidents. If necessary, the sergeant will determine why the incidents occurred and whether some problem is going on at work or in an officer’s personal life.

Sgt. Jeff Baker, left, watches after Officer Matt Austin finishes a scenario with the VirTra judgement simulator at the Omaha Public Safety Training Center.

Supervisors also go through special training to help them help their subordinates, to encourage them to seek outside help and, if necessary, to enforce discipline. The internal affairs unit also could get involved if the behavior doesn’t change.

“We’ve made a lot of advances,” Shaffer said. “It’s about identifying patterns before they become a problem.”

The department also is working with Gallup Corporation on leadership training for higher-level command officers and has handed out an employee survey to, among other things, determine what workplace problems might contribute to excessive-force incidents.

Police seek to defuse potentially hostile encounters with the public before they’re required to use force. Schmaderer said, however, that the use of force sometimes is necessary, especially when officers’ lives are at stake.

“Law enforcement is charged with the duty to protect the public and enforce the law,” the chief said. “As such, officers will regularly find themselves in dangerous and deadly scenarios, and the use of force is sometimes inevitable. What we are looking for as police leadership is proper use of force when the situation arises.”

Contact the writer: 402-444-3100, [email protected]

View original story HERE